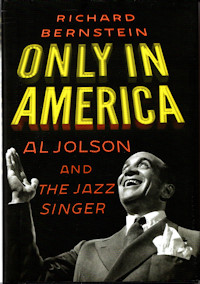

That a book could be published in 2024 centered on Al Jolson, a singularly important figure in Twentieth Century entertainment, who died 74 years ago, and has been effectively marginalized in the media, is itself amazing. Al Jolson was America's first superstar, the most popular entertainer in America for over a decade, and one of the most famous people in the world in the late 1920s. Unfortunately, if you want to learn about Al Jolson, his history, his life, and his legacy, this is not the book in which to find that information. Author Richard Bernstein, whose previous works have primarily centered around China, set out to examine Al Jolson as related to The Jazz Singer, but his book is flawed with errors, omissions, and assumptions.

The majority of the material in Only In America — Al Jolson and The Jazz Singer appears to be derived from several extant works: Mistah Jolson by Harry Jolson, Jolson — The Legend Comes To Life by Herbert Goldman, and The Immortal Jolson by Pearl Sieben. Those books offer an excellent overview of the family background and history of Jolson and his family, a detailed factual examination of Jolson's life and career, and the tales and legends that form the basis for the stories told about this unique entertainer.

The first part of Only In America recounts many of the stories that Harry Jolson related about his family and his siblings, sprinkled with tidbits from other sources describing life in the Pale of Settlement of Tzarist Russia. His description of the observant Jewish life in Europe or in the United States appears to cast it in an unenlightened form. He suggests that his mother's death triggered in him the need to sing "Mammy" songs. That songwriters were writing "Mammy" songs and legions of singers were singing "Mammy" songs seems insignificant. Nor is it noted that William Frawley, a vaudevillian of Catholic lineage, first sang the song destined to be a Jolson trademark, "My Mammy." Bernstein also continually refers to Al Jolson's father as being a cantor, or chazan, in the synagogue. Although he also served as a shochet and a mohel, Al's father was a rabbi, not a chazan. He may have been a rabbi with a good voice, a but that does not make him a chazan. Using those various Hebrew words reflects that within the book, Yiddish or Hebrew words are sometimes italicized, and sometimes not, with no consistency at all.

His stories of Harry and Al's early careers are also fraught with inaccuracies. For example, he confuses important details of the Jolson brothers early vaudeville history when they performed individually, performed together, and when the two formed a trio along with Joe Palmer. Bernstein notes Jolson singing "Mammie," as opposed to "My Mammy." He sets out two stories of how Al Jolson adopted blackface, while ignoring a 1914 article which details yet another tale of the genesis of his applying the burned cork. Jolson's work as a solo prior to and after being part of the Dockstader Minstrels is minimized, and the acquisition of Dockstader's company by the Shubert Brothers (one of the most powerful theatrical forces at the time), which facilitated Jolson's move from vaudeville to Broadway, is ignored entirely.

Those are just the first few chapters. As one progresses through the book, there are many more issues. Bernstein notes the Kaddish prayer as being in Hebrew, although it is in Aramaic. He sets Al Jolson's entry into radio as 1932, it was years earlier. He says that Cantor Rosenblatt sang in Yiddish and Hebrew, the Cantor sang only in Yiddish. He notes songs with incorrect titles, such as "The Old Folks Back Home," rather than "… At Home," he quotes the verse for "My Mammy" incorrectly, and he notes Jolson singing "Blue Moon," not "Blue Skies."

It is clear from the extensive bibliography that much research was done for this book and, in some places, it there are a lot of facts available were crammed into a single page. But often things are a much looser. Some of the material cited gives the appearance of originating on the IAJS website and Facebook page; no source is cited for referenced newspaper and periodical articles. The Society is mentioned once, noting that in 2022 it "publishes a quarterly journal of photographs, historical sketches, and reminiscences, [and] has fewer than five hundred members worldwide."

And, finally, this book on The Jazz Singer includes a group of photos, culminating with one of Al Jolson in cantorial garb, at the pulpit, chanting the Kol Nidre prayer. The photo is captioned as being from The Jazz Singer. It is not. It is from Hollywood Cavalcade, a 1939 film telling about the birth of the talkies, in which Al Jolson recreated that scene from The Jazz Singer for the new film.

If you need to have every book written about Al Jolson on your shelf for your collection, by all means buy this book. But if you are looking for a source of authoritative information, history, or an understanding of why Al Jolson was known as "The World's Greatest Entertainer," not a self created appellation as this book suggests, you would do better with the various books cited at the beginning of this review.

|

Updated 27 Oct 24 |